On Kogonada's Columbus

I first saw the film Columbus in the summer of 2017 at the IFC on Sixth Avenue. I remember the clarifying silence that descended upon the theater as the first wide shot, composed with such care, lit up the screen. Never had I seen my Midwest — the Midwest I mourn when I say I miss home — portrayed so perfectly. Still, years later, I think about this film all the time.

When I am starting a new writing project, I begin with how I want it to feel, and I want this novel to feel like Columbus, to have the same atmosphere. The film somehow manages to be both quiet and loud, both light and dark, both empty and full. There is a beautiful balance to it.

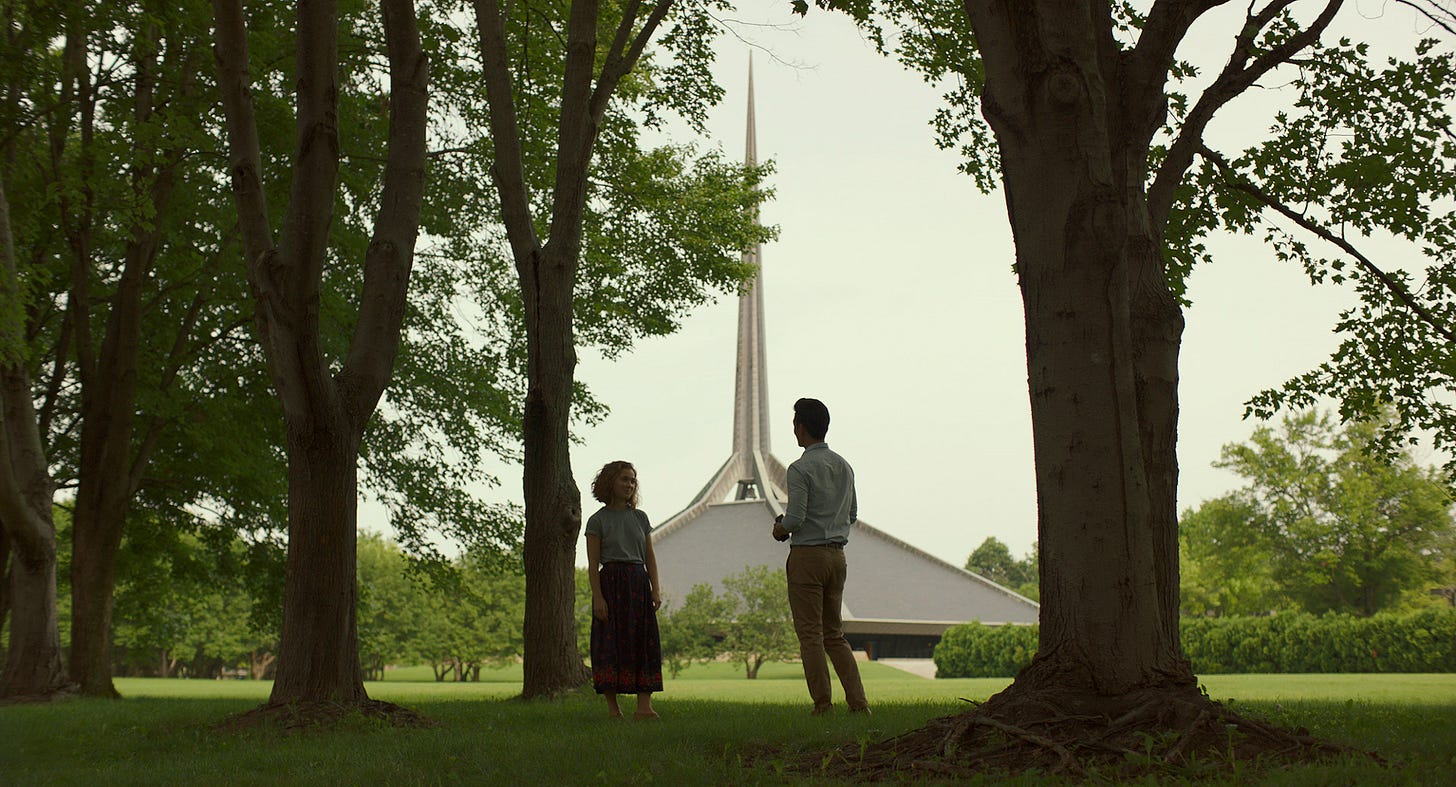

Written, directed, and edited by Kogonada, Columbus is set in Columbus, Indiana, a small town where there just happens to be a ton of famous modern architecture. A young woman named Casey, who loves architecture and dreams of more than her job as a tour guide, meets a man named Jin, who arrives in town after his father, a visiting academic, is hospitalized there. The two build a friendship against the backdrop of awe-inspiring buildings designed by Eero Saarinen and I. M. Pei. It’s not a romance but rather a story of intellectual awakening and coming of age. It’s about family and home and figuring ourselves out.

As part of my novel research, I’ve been reading about the making of the film. This was Kogonada’s first feature film, but he has long been working as a film theorist who makes video essays. In his interviews, he explains his process with astounding generosity, especially in this interview he did with No Film School.

Kogonada says he started with the beats of the story. Rather than thinking about the film as a three-act structure (which is what every screenwriting book tells you to do), he thought of it as having a rhythm and representing a particular period of time between the two main characters.

Then, he took photos of the buildings he wanted to feature in the film and commissioned the illustrator Mihoko Takata to draw art that would capture the spaces and the mood. (Here are her stunning illustrations.) He also collected stills from other films that used the composition he was after.

I know very little about film, but my understanding of film shoots is that many directors will try to capture as much footage as possible so that there’s a lot to work with when editing. Kogonada, on the other hand, went into it determined to make every shot count. He had a specific list of shots he wanted, but just as important were the shots he purposely left out. Columbus is not a film where you see every piece of the story on screen — a lot of the connective tissue is built in your mind as you watch.

As someone who bristles against traditional plot structures, Kogonada’s approach makes so much sense to me. Start with the characters and a period of time. Get the beats down. Get the mood. Decide what you will shoot and what you won’t — or, in my case, what will be on the page and what will not.

One thing Kogonada said that I have been mulling over:

“I knew that I wanted a lot of wide shots — to really see the space and dwell in it, so we often started with the wide shot. Then, we would ask ourselves, ‘Do we need to go in? And if so, why?’”

This feels like the key to the form and style of this new novel, but I’m still trying to figure out what it means in a writing context. I am toying with these scene-setting sections where the reader might expect to transition from setting to character, but instead is left with a lingering image — sort of haiku-like sections to break up the novel’s scenes.

I also think it means not always saying on the page what’s happening in the character’s head. This is my inclination when writing anyway, but I have learned there is a balance. You need enough interiority to care about the character. I think one way to approach this is to have a narrator with plenty of interiority — but one who is practiced at avoidance. In what they do talk about, you understand what they don’t talk about. I’m thinking of certain Lorrie Moore characters who are chatty, but there’s much more under the surface. Or Renata Adler’s Speedboat, where we get so many details but they don’t add up until the very end.

In an interview with The Believer, Kogonada said he’s after the kind of cinema that “lets you cheat on life. It’s not your memory, but it has the shape of a memory, and becomes part of you like the memories of your own life.” And isn’t that how it is with the best art — movies, TV shows, books. These characters become so real to us, we become so invested in their situations, it’s as if it really happened. I think of Jin and Casey, where they are now, whether they talk. I hope Casey’s mom is okay. Most of all, I miss walking around Columbus, where I will one day go, when we can travel again.